by Nina Witjes & Michael Clormann

The image of “Starman”, the astronaut-dummy floating in his cherry red Tesla car through outer space has been all over the media earlier this year. The image was taken from a camera that sits on the car’s dashboard, capturing the dummy, the Earth and a sign on that reads „Don´t Panic”. Both the car and the dummy are a powerful symbol of commercial claim towards space in the age of “New Space”. New Space, a term widely adopted within the aerospace industry, signifies fundamental changes in how we use and relate to outer space: Not only does its goal of commercializing outer space pose a challenging technological and regulatory endeavor, it also introduces new structures, practices and organizational forms of exploration, exploitation, and excitement – in short, a new techno-politics of orbits and outer space. When Starman was put into orbit by SpaceX’s new Falcon Heavy rocket, the impact on the global space community was profound; start-ups, media and government actors alike indulged in an enthusiastic discourse on the promises of commercial space exploration; for space tourism science, business, and to, eventually, becoming multi-planetary.

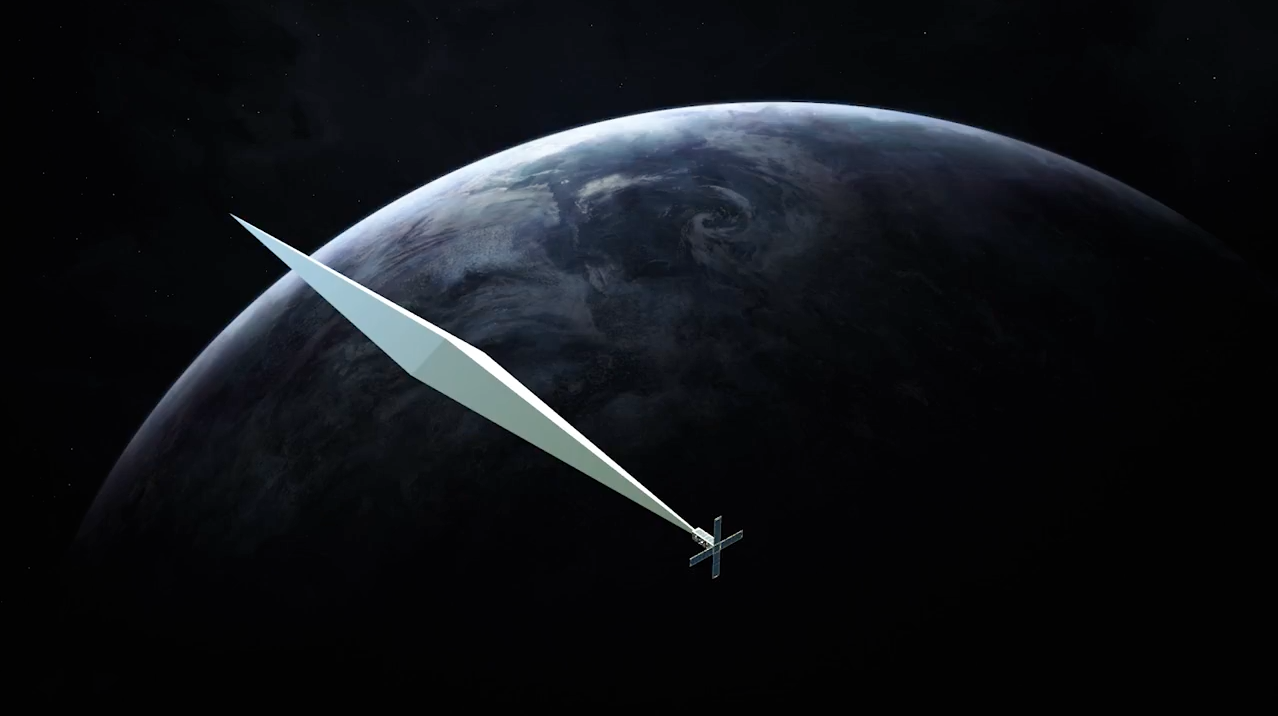

Recently, art has claimed a place in space, too. Trevor Paglen, an artist/activist/researcher known for his work on surveillance and secret intelligence sites, is preparing and announcing to launch a small satellite able to transform into a highly reflective sculpture once it reaches low earth orbit. As soon as crowdfunding allows, the “art satellite” is supposed to launch. The project, in collaboration with the Museum of Nevada, states that „[a]s the twenty-first century unfolds and gives rise to unsettled global tensions, Orbital Reflector encourages all of us to look up at the night sky with a renewed sense of wonder, to consider our place in the universe, and to reimagine how we live together on this planet.“

While it is always a good idea to wonder about humanity and the great and not so great things we did on and with planet Earth, this project – literally – reflects the wrong way. This is, it misses the opportunity to draw attention to many serious issues. In particular that of waste in space. In an interview with PBS , the artist stated that “when I look at infrastructures, and I look at the kind of political stuff that’s built into our environments, I try to imagine, what would the opposite of that be? Could we imagine if space was for art? What would that be? And then I’m kind of ridiculous enough where like, OK, let’s get busy, let’s do that.“

This partly mirrors the attitude of New Space actors like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and others, that is, if we can imagine it, let´s do it – and think about the consequences later, if at all (remember: A car in space can be considered media-effective space junk). At the same time, it reveals the ambivalence with which the space sector approaches its legacy: The remnants of decades of spaceflight activities have left an ever-growing and, by now, a dangerously dense pile of rocket components and defunct satellites in earth’s orbits. This so-called “space debris”, threatening space infrastructures around it, is what many in the aerospace sector now call Paglen’s art project, too.

Not unlike the framing of climate change and marine debris as a socio-material risk of global impact, the worst-case scenario concerning space debris predicts a likely future, where the planet’s orbits are becoming permanently impenetrable to astronomical observation as well as any form of space travel leaving or revolving the planet. That is if no countermeasures are taken. Imagined as a cascading phenomenon of colliding, shattering and thus self-multiplying debris fragments, this scenario evokes immediacy through the identification of a point of no return, again, not unlike the one associated with climate change.

From an STS perspective, we agree with Paglen, that one of the main reasons why space policymakers are still slow to respond to the growing threat of space debris is that it has been largely invisible, as it is “easy to forget these all-but-invisible activities“ taking place in outer space — out of sight, out of mind. However, it is hard to imagine that the orbital reflector will change the way we think about space as a place by „making visible the invisible“, neither in terms of responsibility nor sustainability. Here´s why:

At the time when Paglen began working on the project, concrete fears of space debris had surfaced in public perception through two major and highly visible events in outer space: In 2007, China deliberately destroyed its “Fengyun-1C”, satellite in low orbit, an event heavily criticized as having unnecessarily released large amounts of small fragments of space debris. Two years later, we witnessed the first ever accidental collision of two communication satellites, Cosmo 2251 and Iridium 33, causing over 140.000 pieces of space debris in total. This year, the Chinese space lab Tiangong-1 became a matter of international security concern: From the point when the space station was announced obsolete and defunct by the China National Space Administration (CNSA), the school-bus-size station´s uncontrolled descent appeared as a matter of nightmares for many as its re-entry into the earth’s atmosphere could only be vaguely predicted. The orbital reflector, with its reflective artwork deployed, will be double the size of it.

Instead of making the invisible visible, the Orbital Reflector (as well as any other shiny satellites, floating cars or just the usual clutter in outer space) might be part of the problem: Being in the way of science to gain a clear view of the universe as they limit a telescope’s ability to accurately envision the cosmos and measure its stars.

Jonathan McDowell, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, recently told Gizmodo that launching bright satellites with no other function than art, fun or prestige into orbit, is „the space equivalent of someone putting a neon advertising billboard right outside your bedroom window”. Paglen recently responded to the criticisms, asking why it would be any more of a problem for stargazers than any of the other hundreds (soon to be thousands) of satellites due to launch every year? Well, after all, it is this kind of thinking about the responsibility that has led to severe environmental issues. Regarding the role of art in space and the fact that the Orbital Reflector will revolve around the Earth without any specific scientific or military goal, Paglen asks his critics why “we (are) offended by a sculpture in space, but we’re not offending (sic!) by nuclear missile targeting devices or mass surveillance devices, or satellites with nuclear engines that have a potential to fall to earth and scatter radioactive waste all over the place?” But is this really the case? After all, it has long concerned social sciences how to make infrastructures visible and how to deal with the sociotechnical vulnerabilities of any techno-society. In particular, researchers in science and technology studies and critical security studies have shown an emerging interest in questions of surveillance from and the increasing militarization of outer space as well as the risks these and their byproducts pose for the sustainability of earthly and space infrastructures. Discarding the Orbital Reflector as a bright idea should not be understood as a rejection of art concerned with and located in space, but of the claim that if the military can launch satellites, art should, too.

Simultaneously, critical debates about the role of art in space are not necessarily in favor of or naive about governmental space technologies. There are civil society projects, too, that use satellite images for monitoring human rights violations and war atrocities – often operating on a shoe-string budget. Many of them would probably be happy to see the 1.3 million dollars estimated for the construction and launch of Paglen´s activist art project to impact their activities. Instead, its contribution will be to shed light on places that are currently in the dark – not metaphorically speaking in terms of human rights but just because it´s nighttime.

Space has become a place where sustainability is increasingly negotiated as an issue of security, as billions of people around the world rely on space systems to facilitate their daily life, from navigation to environmental services, from science to communication, crisis response and banking, from intelligence to education. Space debris poses the question of how we want to live with our material leftovers revolving “above” of us. Another bright and shiny useless satellite in orbit does not provide a good answer.

Nina Witjes is a university assistant (post doc) at the Institute for Science and Technology Studies at Vienna University. Her work is situated at the intersection of STS and International Relations with a special focus on space programs and security.

Michael Clormann is a doctoral candidate / research associate at the Friedrich Schiedel Endowed Chair of Sociology of Science and the Munich Center for Technology in Society at the Technical University of Munich.