By Kamiel Mobach

How many people are currently affected by the coronavirus, nobody really knows. Governments and their organizations are publishing figures every day, but this does not say anything about how many people actually carry the virus with them. Knowing this number accurately would be impossible, because the way in which such knowledge is produced is quite complex. In this post I will shortly illustrate that there is no objectivity in numbers. As an alternative, I will suggest the notion of ‘legibility’ as a view on what numbers can do for societies and governments. I will connect this concept to issues of responsibility and politics.

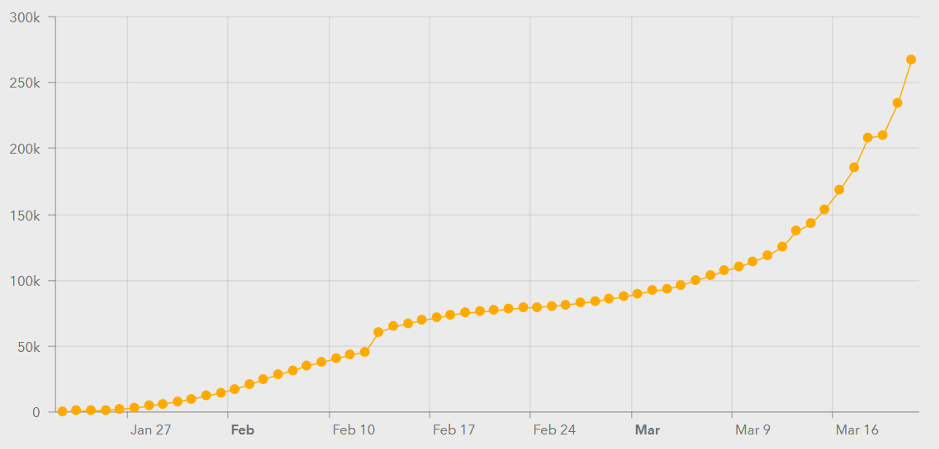

The sudden, discontinuous increase in this graph on the 13th of February was the result of the Chinese government changing its definition of coronavirus cases to include people with symptoms who hadn’t been tested yet. The number of people who were being treated in Chinese hospitals did not change, but from this day onwards more of them were counted as ‘patients with coronavirus.’ More recently, many governments have stopped testing every person that has got symptoms. At the same time, most of them still publish numbers solely based on positive test results. Not testing everyone is justified by the fact of limited testing capacity. However, the continued publication of figures based on test results brings about unclarity about how many coronavirus patients there currently are. In the Netherlands, for example, the Dutch governmental public health institute reported 1135 cases on 15 March, while the country’s municipal health services said they estimated the number of infections in the country to be around 6000.

Statistical knowledge, like the figures just discussed, is an arena where practices of government and science are intimately intertwined. In his book Seeing Like a State, James C. Scott develops the concept of legibility to theorize this intertwinement (1998). The book gives a host of examples of how states developed formal knowledge categories in order to know more about their population. Examples include standardized measurements and weights, land surveys, mapping and building of cities, and census. Scott argues that the categories that the state uses to make things legible do not just describe how things are, but come to prescribe how people live, how land is organized and how people distribute and trade resources. However natural they seem to us now, surnames, as well as birthdays are artifacts of census practices imposed on our ancestors centuries ago.

In the current case of the coronavirus, the state has to impose means of categorization to define certain people as infectious, and to classify people into different categories of risk. The sudden increase in the number of coronavirus cases on the 13th of February is an example of how the state knows differently through different categorizations. There is a whole apparatus behind the numbers that get shown in the media. There are people who administer tests, labs that process them, administration that keeps track of the numbers, and in all these stages and links of the process, choices need to be made about how to proceed. This can result in certain people not being tested, for example because they have not been in a risk area in the past weeks. Moreover, what counts as a ‘risk area’ is changing almost daily. The limited capacity of testing means that there are assumptions at play in who can be defined as a coronavirus patient. On top of that, there are multiple ways to test someone: for example, there are tests that find molecular signs of infections, tests that look for antibodies against the virus, as well as CT scans of a patient’s lungs. There are certain standards agreed upon that are not the only possible standards that could have been chosen.

None of this means that coronavirus patients are a made-up category. Instead, the discussion of ways of knowing about the coronavirus shows that making knowledge is a complex practice. What I want to focus on here, however, is not the way in which single patients are categorized, but how knowledge is created about a population. In the case of the before-mentioned increase, the Chinese government had to justify measures it was taking to stop the spread of the virus. It could do this only by convincing the public, organizations, other lawmakers and foreign actors that the measures it was imposing were justified. The population became a patient that needed to be categorized in order to decide and justify what the right ‘medicine’ would be.

The justification of certain measures over others depends on how they are made legible. Using a method that results in lower numbers might inspire inaction, whereas using a method that results in higher numbers might inspire rash measures to contain the spread. Therefore, legibility provides two intertwined functions: it makes governments able to know about the people and things it has power over, and it provides justificatory measures for policies it decides upon. People and groups think differently about which measures are justified. As there are many stories going around about what is happening, how many cases there could be and what the governments’ next measures are going to be, it is hard to find a conclusive story to believe.

The statistics that governments and other institutions provide can help explain their choices. Inversely, which strategies of counting and categorizing are used also depends on the measures that need justification. And this depends on what we see as the thing that needs to be cured. Is it the disease in specific people? Is it the epidemic in a population? And if so, in which population does it need to be cured more urgently and about which places do we care less? Maybe it is a specific country’s healthcare system that needs to be held upright. To do this we could try to ‘flatten the curve’, i.e. spreading the cases of the disease over a longer time in order not to go over hospital capacity. Doing this, however, stands in contrast with keeping the economy running in the most profitable way. To let businesses survive the crisis, it would be better to lower the lockdown time. Instead, looser measures could be chosen for by propagating the notion of ‘herd immunity’. Governments could also support the economy, but to whom should they give their newly created money? Big businesses? Self-employed people? Small businesses?

Having these matters of concern in mind, we see that the statistics published about the coronavirus can respond to different worries and fears. This begs the question whether we should publish numbers about cases around the world, in specific continents, in specific regions, or countries. Which ‘unit of people’ we publish about and where we draw boundaries between these units stands in relation to the possible responses. Making the coronavirus epidemic legible, then, is not just something that has to do with abstract knowledge-making but is an act of responsibility towards certain concerns.

Choices have to be made here, though. We cannot be responsible to all possible concerns around the epidemic, because some of them clash. We cannot keep the economy functioning like it is and at the same time stop the spread of the disease. Moreover, attention to some concerns, like keeping the Austrian healthcare system functioning, draw away attention from others, like the spread of the virus in refugee camps. On the other hand, a concern for situations farther away from home might be linked to concerns about one’s own region if thought through properly. European governments were quite inattentive to the situation in China when the virus did not spread to Europe yet. The way in which the situation evolved shows that such inattention is no option in our globalized societies.

Taking these thoughts into account, it is important to demand public access to the way in which figures about the pandemic are being created. On the website of the Austrian ministry for social affairs, for example, the government publishes how many people have been tested and how many of those tests were positive. The website explains that a test is conducted when a ‘health officer’ reports a potential case of the disease. This does not explain which decisions this officer should take to decide whether a potential patient is going to be tested. It is important that such information is made available to evaluate the justifications that governments use to implement certain measures. When governmental authorities show certain graphs to justify their measures, we should know what these graphs show, whether the shown in- or decrease in cases represent patients in hospitals, tested patients, or an estimate of the number of patients.

It will be very interesting to witness the discussions on what is worth a proper response and what is not during the rest of the pandemic and during its aftermath. The outbreak has opened up cracks of social inequalities that have been unethical, if not outright dangerous to societies all over the world. When people do not have access to healthcare, for instance, the disease spreads faster. If people are forced to keep working while they are ill or at risk of getting ill, they will take more risk and possibly spread the virus. If hospitals are incentivized to compete on a ‘health care market’, they will increasingly push away extra capacity to deal with emergency situations. Moreover, we will see for which populations governments are willing to take measures and spend money and for which they won’t. Which economical actors will get compensation for the production capacity lost in the past weeks and which won’t?

Another big question confronting us is how the current crisis will affect the attentiveness to future threats that are further from home. This is connected to the insight that in a globalized world, it is impossible to hide and protect your own while leaving others to their bad fortunes. How do the processes of making the coronavirus crisis visible and the swift responses to it compare to how the climate crisis has been made visible over the past decades? What about research on social inequality? It seems that making something legible does not directly translate into action from governments and society. Nonetheless, the way in which we make these threats visible, where we draw the boundaries between units of analysis such as populations, will have big effects on the measures taken in these future crises.

I want to thank Ruth Falkenberg and Isabel Frey for their very helpful critique and suggestions.

Kamiel Mobach is a PhD student at our STS department researching the co-production of the scientific and sociopolitical identities of the ‘European Organization for Nuclear Research’ (CERN). He is interested in the historical evolution of notions such as ‘fundamental research’ and ‘objectivity’ as well as their sociopolitical functions.