by Kaya Akyüz

Recently, I have learned that a genetic genealogy platform had been used by the US justice system in order to find a serial killer. My genome was one of the hundreds of thousands on this platform that allowed the investigators to spot the killer and as users of the platform, we have learned about it only after the press reported on the issue. Should genomic data in genealogy or personal genomics databases be used to simply catch a criminal or for similar purposes?

We are giving out data all the time willingly or unwillingly, knowingly or without even noticing. Our faces and license plates get recognized by cameras on streets, consumption habits are recorded, GPS signals are tracked and many more. Sometimes this is for “the public good” as in the case of surveillance for security and often it is for commercial purposes. However, the majority of these different forms of data collected resemble each other in that they originate from an individual: individual´s behavior, preferences, environment or social network. One other form of data that is increasingly produced in large amounts is genomic data in the numerous databases that function as biobanks and repositories for genetics research. The genomic data landscape also includes direct-to-consumer (DTC) genomics companies (e.g. 23andMe) to which millions of users send their spit to learn more about their traits, ancestry, health risks and biological relatives.

Everyone has a unique genome and when sequenced, it can be converted into a text of approximately 3 billion characters with four letters: G, C, T, A. Genome as data is different than other types of personal data because it does not simply originate from an individual, but bits and pieces shared by many different people come together through reproduction. While all humans carry almost the same genome sequence, the remaining minuscule differences increase as one moves away from the closest relatives to distant relatives, including each and every one of 7.5 billion people on earth. This way, genomic information allows an individual, e.g. an adoptee, to identify unknown biological relatives; however, it also means that an individual can never be anonymous unless all (close) biological relatives of the individual anonymize their genomic data. I will exemplify this with the controversial case mentioned in the beginning and explain why there is a need for urgent societal discussion about what “personal” data means and who is to decide, when we consider the human genome.

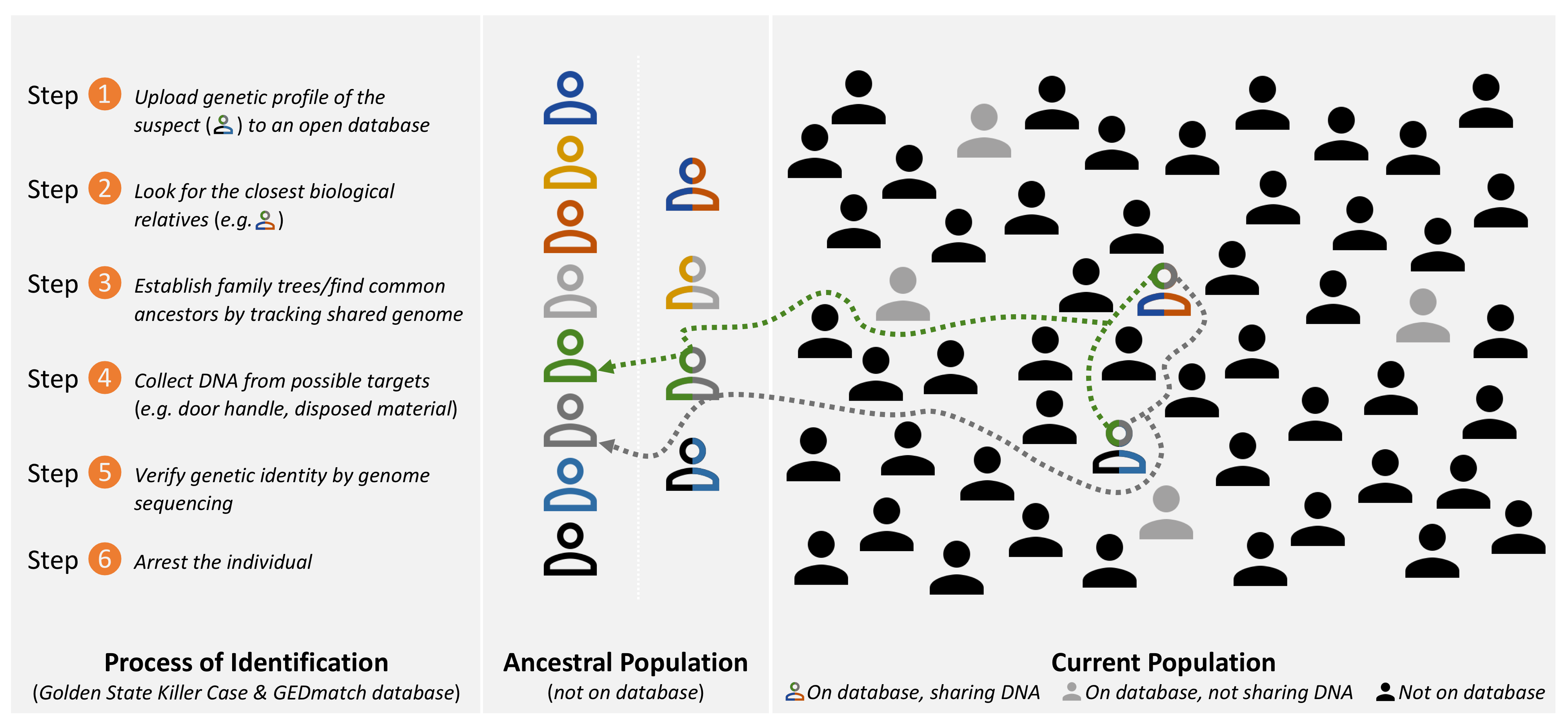

Along with genome editing in human germline using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, the most controversial biotechnological application in 2018 is probably the identification of the Golden State Killer, who is claimed to be responsible for 13 murders and numerous rapes in California in the 1970s and 1980s. Although the DNA had been collected from the crime scenes, the perpetrator had not been identified because his profile was not in the databases. With the help of the genetic genealogist Barbara Rae-Venter, named one of the ten people who mattered in 2018, the US justice system opened the doors to a debatable practice. The investigators produced a genome profile of the Golden State Killer from decades old crime scene material and then they uploaded it to an “open access” genealogy platform: GEDmatch. Customers of different genealogy companies (i.e. 23andMe, AncestryDNA, FTDNA and others) have been uploading their raw genomic data to GEDmatch in order to identify biological relatives that are in the databases of other companies, without needing to buy their services. The authorities used this opportunity to identify the closest relatives of the suspected perpetrator and tracked back the suspect through constructed family trees and common ancestors to a person, who happens to be a former police officer: Joseph James DeAngelo. And this is only the beginning. According to Nature and the New York Times numerous cases are underway with a similar approach. A rapidly growing cottage industry is emerging between genetic genealogy and criminal investigations without a chance to publicly discuss what this means for the ordinary individual, her genomic data, privacy and anonymity, especially considering that this system is amenable to many uses beyond identifying serial killers. As long as there is a biological sample and the identity of the owner is to be found, the system visualized below would serve the purpose.

How was the suspected Golden State Killer identified using an open genealogy platform? With a simplified visualization of the process, here I show how shared ancestral genomic variations (noted with colors) allow finding links between an unidentified individual (using left tissue, in this case from crime scene, but possibly from a door handle, a glass etc.) and self-identifying individuals on an open genomic database without knowledge of either.

Identification of a notorious criminal does not leave enough room to discuss the ethical considerations around the use of ordinary individual’s genomic data; besides, who would (dare to) be against a system that allows to track down a serial killer? If it were not for the lax policies of GEDmatch regarding the use of genomic data of its users, the Golden State Killer had not yet been identified. After all, there are numerous databases that are bigger than GEDmatch, but a similar search in these would generally necessitate a court order due to policies of these public or private institutions. As a person, who has his genome data on GEDmatch since many years for genealogical purposes, I find it ethically unacceptable that law enforcement agencies uploaded crime scene material and used hundreds of thousands of profiles to find the relatives of the criminal, followed links through their lives, all of which took place without the users of the platform being informed.

The controversy seems to have become a breaking point in our understanding of genome data and anonymity. Science reports that a sample that encompasses only 2% of the American adult population (only four times that of GEDmatch) would allow 90% of Americans to be identified even if they have no genomic data in any database (60% is already identifiable with GEDmatch). This means uploading one’s own genomic data to such a database with real name or similar identifiers is no longer a mere personal decision unless the individual accepts being a “genetic informant” in searches that may lead to stigmatization of innocent individuals, risk legal protection against discrimination or even out the identities of distant relatives, who may be a sperm donor, an undercover agent, an “anonymized” individual who took part in a biomedical study, or just a person who drank from a glass in a restaurant followed by a stalker.

Waiting for individuals to anonymize their genomic data seems to be an option out of this problematic path. However, this means that those who decide not to anonymize their genomes, decide at the same time not to allow their relatives to anonymize themselves. If we are concerned about our anonymity, we have to push forward global regulations that encompass all platforms, companies or biobanks to remove identifiers attached to genomic data such as names and last names, year or place of birth, at least in a way that protects anonymity unless there is a court order. Otherwise, this is the end of anonymity as we know it. The post-genomic future holds numerous risks along with opportunities and we have to be aware that seemingly personal decisions are made on others’ behalf, often unbeknownst even to the person making the decision.

So the question is, is it “my genome, my decision” or “our genome, our decision”?

Kaya Akyüz is a PhD student and uni:docs fellow at the Department of Science and Technology Studies of University of Vienna. Having finished his bachelor and master’s studies in Molecular Biology and Genetics at Bogaziçi University, his current research is on the dynamics of making and unmaking a new field in science through the case of genopolitics, an emerging research field at the intersection of political science and genetics.