by Magnus Rust

This is a story of how the latest technologies have changed our way of collaboration, and why this change is invisible. The center of this study is a mundane object. An object millions of students worldwide have encountered. They weren’t confronted with the very same object every single time but with different expressions of the same idea. We are talking, how could it be otherwise, of the seminar handout. More specifically we will turn our attention to multiple iterations of a specific handout issued by the Viennese STS department in the last eight years—the handout of the annual course “Risky Entanglements? Theorising Science, Technology and Society Relationships”.

Brief History of the Viennese STS department

It was the year 2010 when the Viennese STS department took another important step in its history. After the English-language MA program had been established a year earlier, the department moved from a classic Altbau in Sensengasse 6, where it had been located since 1988, to its modern location, the NIG (Neues Institutsgebäude) in Universitätsstraße 7.

Since its dawn in 2009, an integral part of the master’s program “Science-Technology-Society” has been the “case-based learning” approach. Newcomers are split into small groups and given an emerging topic in STS. Now it’s the group’s task to write a full-fledged research exposé that could (theoretically) be handed in in a real world situation. From zero to 100 in only one semester in a field not well known to all of the students. A challenging task but also quite rewarding when finished. Not surprising that this case-based-learning approach won the Teaching Award of the University of Vienna in 2014[1].

This cased-based learning phase consists of a bundle of seminars, lectures, tutorials and feedback sessions. One of the five core classes is the aforementioned “Risky Entanglements? Theorising Science, Technology and Society Relationships” first offered in WS 2009, this year taking place for the 14th time. The “Risky Entanglement” is one of the staples of the STS institutes. At the same time, the STS department had been in flux. After Helga Nowotny had founded the original STS department in 1988, Ulrike Felt became, after 10 years as an assistant, a professor in 1999. Maximilian Fochler became the second professor in 2012 and Sarah Davies has been holding a third professorship since 2020. Not to forget all the students, PhD candidates, postdocs, or secretaries who have worked at the institute over the last decades.

But not only has the staff changed but also technologies, societies, the zeitgeist. It would be of great interest to investigate the topics researched at this institute in the last decade. But it is also equally interesting to not just analyze the works of this institute but how those works worked; how work was done, and how the teaching was organized. All of this follows a key concept in STS called “symmetry”: the idea that reflexive modes cannot only be applied to a research matter but also onto your own research methods.

Changing layouts

Here, we finally return to the handouts, more specifically the handouts of the core course “Risky Entanglements” from 2013 to 2020. Upon closer inspection, they provide insights into how digitalization has shaped the production of those documents. Even if not visible directly, those eight handouts represent a curve from a collective to a collaborative praxis of writing.

A handout—sometimes also called syllabus—is a staple of a student’s life. Its purpose is to comprehensively communicate what a given seminar is about, what is expected for the seminar sessions and how the seminar will be graded. From my personal experience in the field of humanities, I can tell you that there is a big variety of handouts. Some are very precise, others just create confusion.

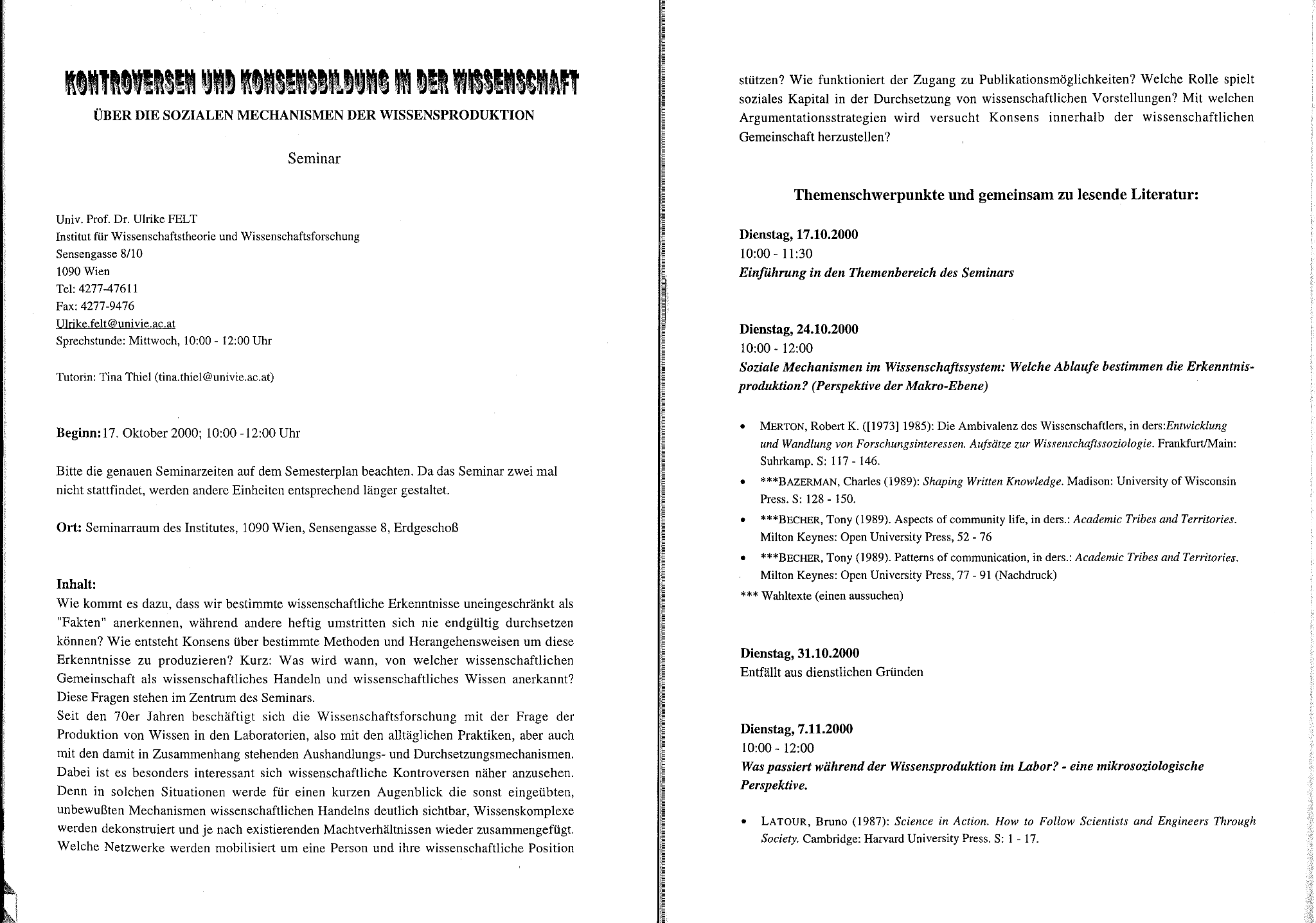

You can say the handouts of the Viennese STS department were quite solid right from the start, like one syllabus from 2000 shows:

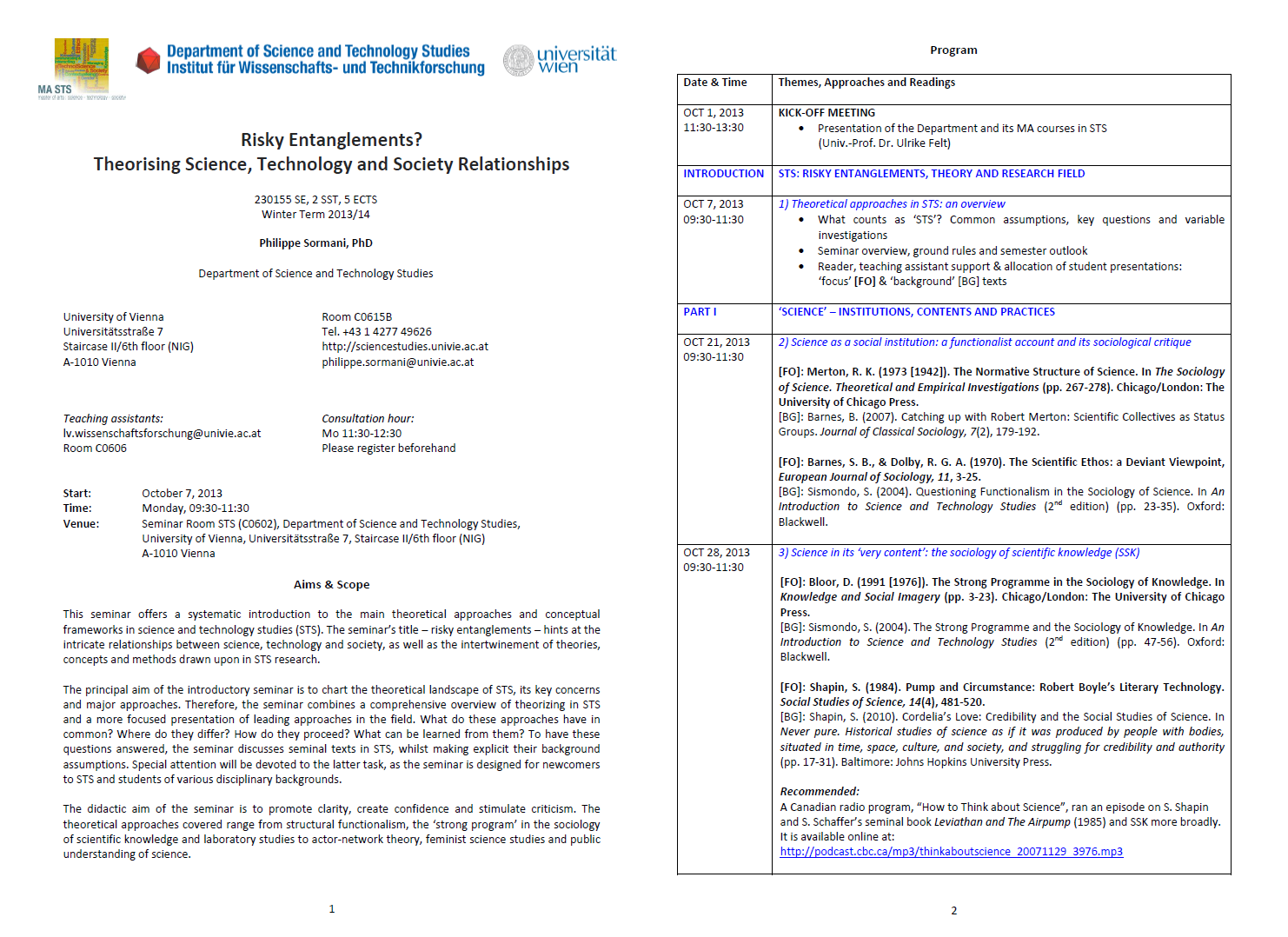

This proven design echoes in the first handout for “Risky Entanglements” 13 years later:

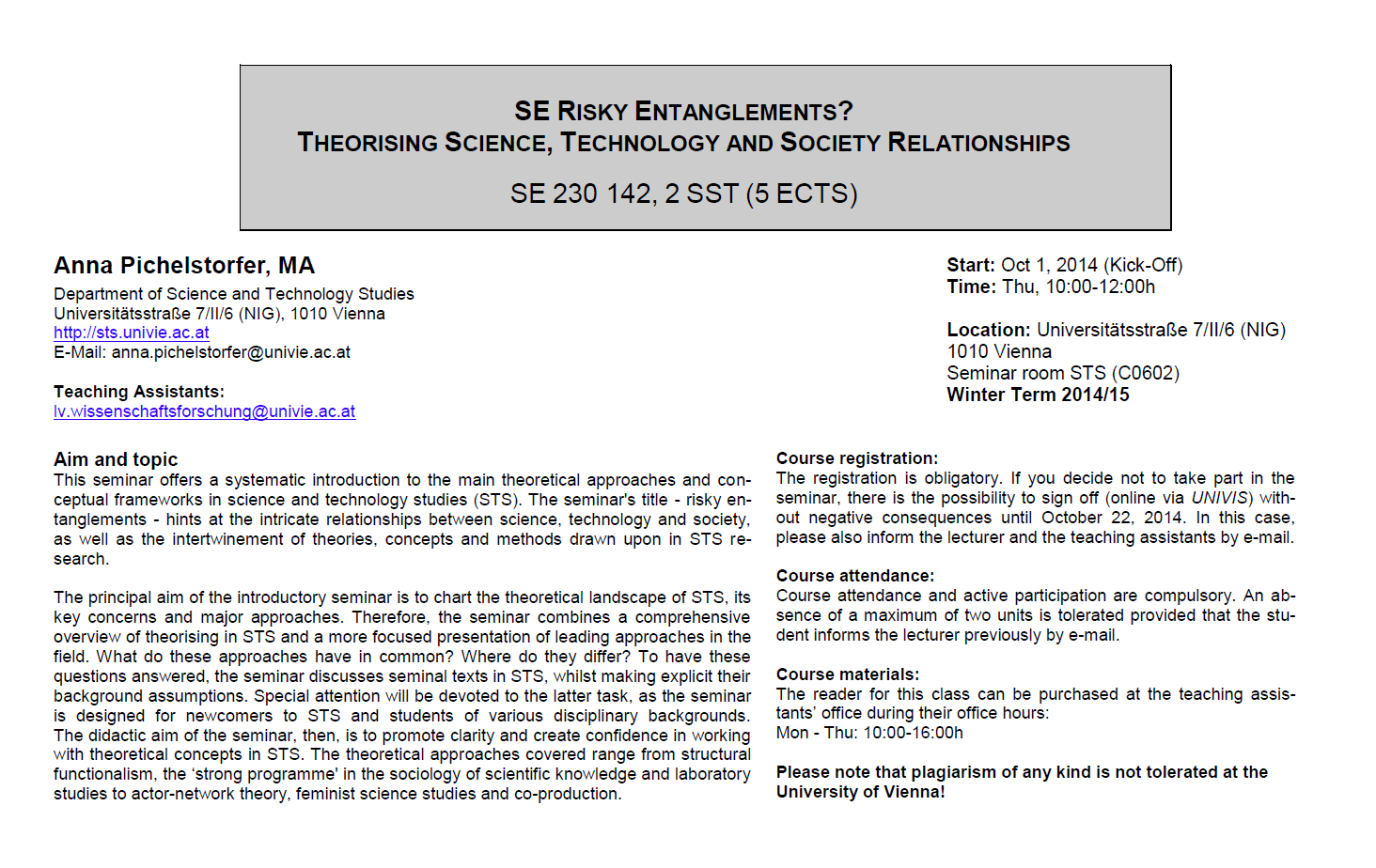

The design in general has become ever clearer, a department logo has been introduced and color is used to communicate even more effectively. The next iteration of the course one year later lands with a surprise. All the established information bits are still there but the text direction has changed:

“Corporate amnesia” and its solution

But why was the text direction and design changed? That is not that easy to answer, mainly because “corporate amnesia” (Arnold Kransdorff) is at play. This is a classic problem of “organizational memory”[2] or of “tacit knowledge” (Michael Polanyi) to use an STS term. It assumes that for operating any institution—whether company or university—successfully, much more knowledge is needed than what’s in the manuals. Knowledge that might not even fit in a written manual and is thus at risk of getting lost easily. When people leave an institution, much of this tacit knowledge often leaves as well.

The idea of “corporate amnesia”, however, is much older than management literature. It has been discussed for a long time and has been problematized in many fields, for example, in the discipline of history. It was Jules Michelet, a patriotic French historian and popularizer of the word “renaissance”, who wrote in 1846: “My inquiry among living documents taught me likewise many things that are not in our statistics.”[3] What he meant was that he was not only trusting the dead paper documents for his historiographies, but also seeking contact with “living documents”, that is humans. He made Oral History a staple of his analyses, also collecting French fairy tales.

Why the design was tilted is not exactly known, but it might have something to do with the media situation in 2013. Maybe the handout was not only provided digitally but was also printed and hung on the institute’s walls? What is more telling is that such a drastic design change was even possible. In 2013 there were 4 competing handout designs and even more variations at the institute, differing among staff members or guest professors (though the content structuring was pretty much the same throughout).

A disruptive change

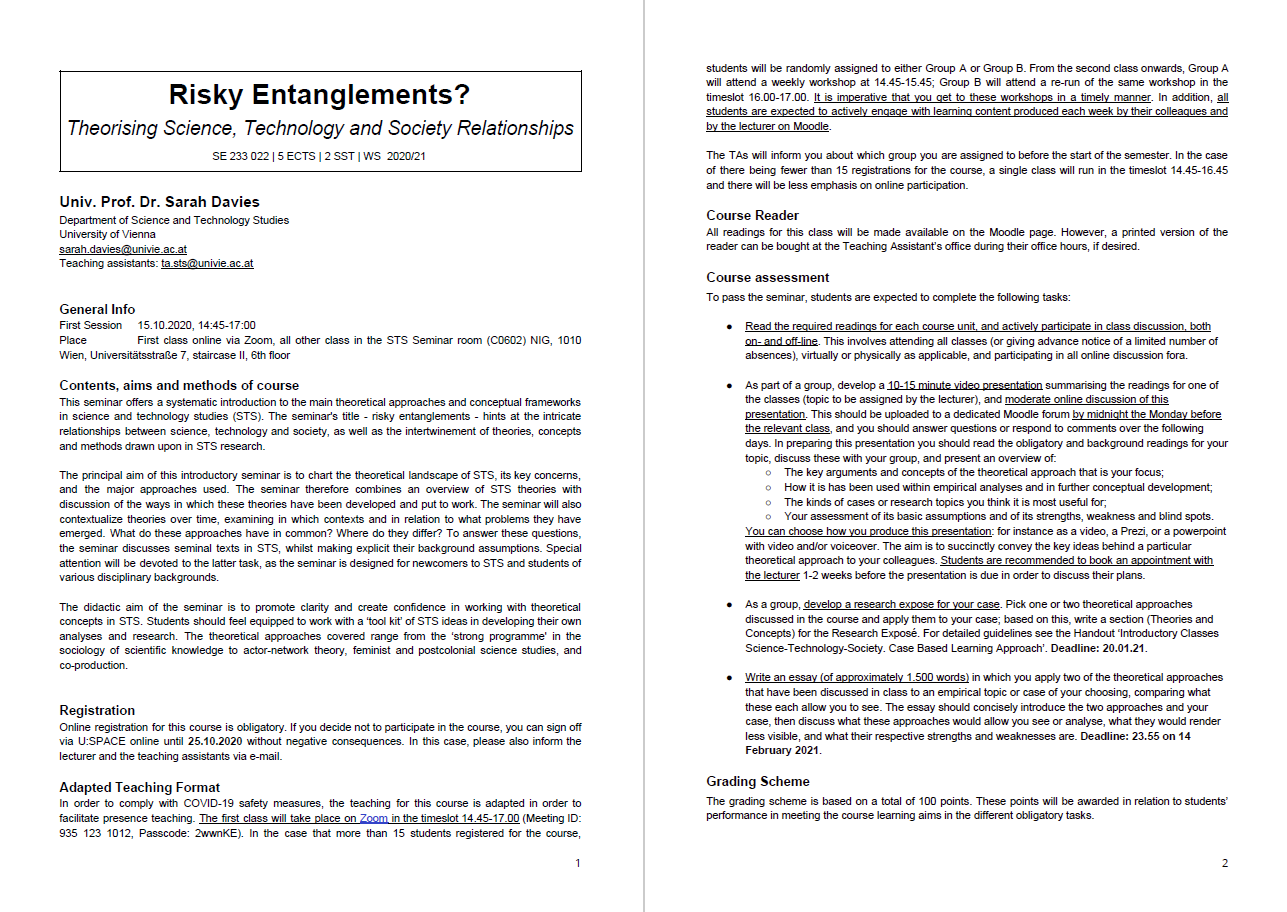

This hotchpotch ended in 2015. Even though the lecturer for “Risky Entanglements” stayed the same, the design was adapted once again. From that point in time all STS handouts would follow a corporate layout that seems to have stayed unchallenged to this day. The only adjustment was that from WS 2015 to WS 2016 when the handout font was switched from Calibri Light to Arial:

This very last change seems to be the most neglectable detail of all but is in fact an indicator for the most disruptive change in handout preparation at the institute yet. It was in WS 2016 that the handout production was converted from offline to online. In previous years, word documents were sent between administration and lecturers for pinning down dates, contents and synopses. A tedious process that can be even more annoying if the two parties operate with different software versions.

In 2016 the institute’s administration started using a cloud-based service for the creation of the handouts. It seems like the seminar “Science, Technology and ‘the Law’” by Xaq Frohlich in WS 2015 was the test run for this practice and was subsequently adapted for all handouts to come. It makes sense: Frohlich was a guest professor, so communicating dates was more difficult than just walking to the office next door.

From collective to collaborative writing

But what is the disruption here? It was the switch from a collective act of writing—people work in the same handout but send clearly distinguishable versions around—to a collaborative act, where, at the end of the day, nobody can trace back what person contributed which part [4]. Wikipedia, founded in 2001, is a prime example of collaborative writing (even if technically it is possible to trace every change made back to a specific user account).

That was the giant leap: from collective to collaborative. Simultaneous instead of linear. From server-bound to de-central. Internet instead of Intranet. This allowed organizational re-configuration. The cloud document can be shared with external lecturers, always allowing them to access the latest version without being constantly bombarded by the STS institute with edited work-in-progress pieces.

It’s a bit like Schrödinger’s cat on demand: If you want to know about current status you can access the online document. If not, you won’t know the latest version, or whether there is even a newer version available. And like Schrödinger’s cat, at one point in time the status’ uncertainty is resolved. The handout is finished. The cat is dead. Every new observation will deliver the same result.

References:

[1] University of Vienna: Universität Wien verleiht Lehrpreis UNIVIE Teaching Award 2014, Blog (05.06.2014), https://medienportal.univie.ac.at/presse/aktuelle-pressemeldungen/detailansicht/artikel/universitaet-wien-verleiht-lehrpreis-univie-teaching-award-2014/)

[2] James P. Walsh & Gerardo Rivera Ungson: Organizational Memory, in: The Academy of Management Review 1(16), 1991 (pp. 57-91).

[3] Jules Michelet: The People, translated by C. Cocks, London: Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans, 1846, p. 2.

[4] cf. Kathrin Passig: Schreibende Staatsquallen, in: Dorothee Kimmich et al. (ed.): Verweilen unter schwebender Last. Tübinger Poetik-Dozentur 2015, Künzelsau: Swiridoff, 2016 (pp. 69-86).

Magnus Rust is a student at the Department of STS, University of Vienna, with a background in Cultural Studies and journalism. He is interested in historic developments of technologies big and small and their contemporary social ramifications.