By Thomas Kuipers

Corona app illustration (stock image from pixabay.com).

Corona app illustration (stock image from pixabay.com).

There’s an app for that

The desire to solve society’s problems with technological fixes is not new. They appear to be cheap, efficient and immediate. On the contrary, political and systemic responses are expensive, slow, and controversial. Often, we are not even sure what exactly political responses would entail, or how they would be realized. Typically, they foster heated debates, which appear to slow down this already lengthy process even further. The appeal of putting science and technology in the drivers’ seat is obvious.

In this regard, the coronavirus pandemic is no exceptional situation. It was not long before we vested our hopes of tackling this crisis in technology. A solution was formulated within the sociocultural context of recent mass adoption of smartphones, which came along with a plethora of apps designed to solve all of our problems, inconveniences and more. The echo of Apple’s commercial “There’s an app for that” has yet to fade. Perhaps it was not surprising that we imagined that an app would come to the rescue. In some nations, such as Australia and the Netherlands, the mass adoption of a ‘corona app’ was even listed as a hard requirement for lifting the lockdown. The Dutch government organized an ‘Appathon’, in which seven companies competed for a weekend to create an app that would be used to “combat the coronavirus”. What exactly the app should do was unclear, but that the coronavirus could effectively be fought with an app was taken as self-evident.

Roadblocks to an imagined future

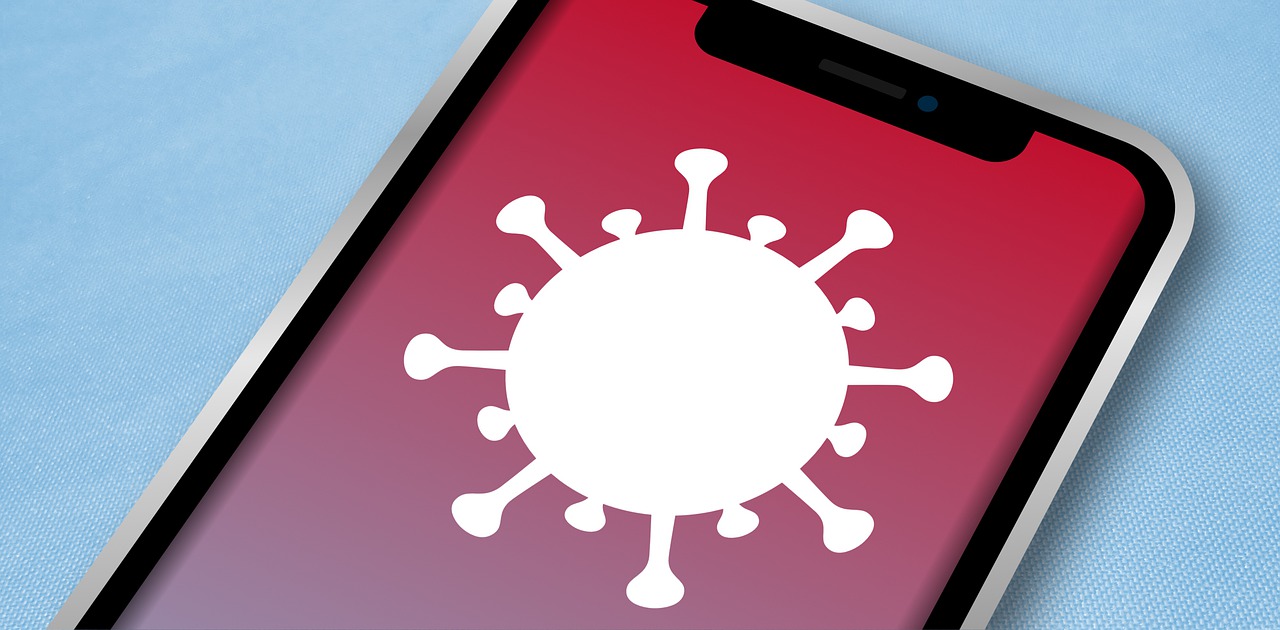

Fast-forward one month and it appears that a particular type of corona-fighting apps has taken the center stage: one that facilitates contact tracing via Bluetooth. When two people have the app installed on their smartphones, they automatically exchange pseudo-random messages (hashes) with each other when they are within the reach of each other’s Bluetooth signal. Each person with the app keeps track of which messages it has received. When someone then gets infected with the coronavirus, an alert will be sent to all other participants via the internet. This alert, which contains another hash, will then be compared to all of the previously stored Bluetooth messages. If a match is found, this would mean that the participant has been within the vicinity of the now-infected patient, and is at risk of also being infected.

Even though little is known about these apps as of now, both proponents and opponents have been engaging in a hot public debate. It often appears that the choice of resorting to contact tracing apps is a matter of balancing public healthcare with privacy (Verhagen & van Gestel, 2020). Will contact tracing apps successfully “combat the coronavirus”? Or will they upend privacy as we know it? The only real answer at this point is: we have no idea. At this point in time, “the technology remains the figment of a particular technoscientific imagination” (Stilgoe, 2015, p. 6). Studying contact tracing apps means studying ideas, promises and imagined futures. Their very existence and their actual qualities are still being negotiated from various technical and political angles.

The technicalities of Bluetooth have thus far already played a major role in shaping these apps. On iOS, it is currently only possible for an app to send and receive these Bluetooth signals when the app is active and visible on the screen. When the phone is on standby, which it always is when it is in your pocket, the Bluetooth messages cannot be sent. On Android, it is possible for apps to send and receive Bluetooth signals when the phone is in standby mode. However, fears about battery drainage and reliability across a wide range of Android devices remain. These limitations on access to Bluetooth have been perceived as insurmountable by certain European officials and they have requested the tech giants to remove these restrictions. Initially, Apple and Google flat-out refused to do so on the grounds of protecting the privacy of their customers. Not much later, a French “senior government official” proclaimed that “European states are being completely held hostage by Google and Apple” (Rosemain & Busvine, 2020). One cannot help noticing the irony in European states demanding Silicon Valley tech giants to lift their privacy-protecting measures.

A particularly empty snapshot of Museumsquartier, here in Vienna. Busy places like these could be regular ‘meeting’ points for our phones’ Bluetooth sensors (image taken by the author).

A particularly empty snapshot of Museumsquartier, here in Vienna. Busy places like these could be regular ‘meeting’ points for our phones’ Bluetooth sensors (image taken by the author).

The political difference between an app and an API

These tech giants are now in the unique position to program the capability of Bluetooth-enabled contact tracing into our smartphones. They have been building the infrastructure of mobile connectivity for over a decade, with themselves firmly established at the heart of it. Building this global infrastructure is not a purely technical endeavor, it also “requires organizational, economic, political and legal innovation and effort in order to resolve the heterogeneous problems that inevitably arise” (Edwards, 2010, p. 10). While many individuals, institutions, businesses and governments are dependent on this infrastructure, Apple and Google hold a disproportionate amount of power over who gets to access or modify it.

Soon after the rallying cries of frustrated politicians, Apple and Google announced they would contribute to solving this global problem with a new collaborative effort between the two rivals, titled “Privacy-Preserving Contact Tracing”. A crucial element of this effort is an Application Programming Interface (API) which enables apps to interact more smoothly with the Bluetooth protocol. Through this API, developers can access all the data necessary to create contact tracing apps. What is remarkable, is that Apple and Google are not creating a full-fledged contact tracing app themselves. They are merely providing the building blocks for others to do so, even though the two most powerful technology companies in the world certainly have the technical capabilities to create this app.

While we can only speculate whether this was a deliberate strategic decision, it certainly puts Apple and Google in a significantly less politically controversial position. ‘Corona apps’ and their advocates have come under great scrutiny in the media by privacy-guarding institutions and worried politicians. If Apple and Google were to develop the app themselves, they would surely attract the bulk of this storm of criticism, but now they appear to be shielded from at least part of it. We can only begin to imagine the kind of public and political backlash they would face were they to undertake the development of the entire app. To understand why the decision to only develop an API and not an app appears to be less controversial, we need to concern ourselves with what makes for controversy in the first place.

A common conception in contemporary societies is that technology develops independently of social and political forces (Wyatt, 2007) — it is even often believed to be neutral and value-free. This causes what is seen as purely technical to be shielded from scrutiny. Because engineers supposedly follow an independent and technocratic path of innovation, we need not worry about it: their innovations will take place regardless of societal debates. This conceptualization of technological progress is known as technological determinism. Quite on the contrary, the political is understood as an arena of debate in which collective decisions are made. Democracy — the rule of the people — surfaces as the antithesis of the technocratic notions of technological determinist thought. While these readings of technological progress and political decision-making appear as starkly separate domains, the boundary between them begins to blur as we realize that the design and development of corona apps is a highly political endeavor. Where exactly lies the boundary between the technical and the political and how does it emerge? Can we say that apps are always political, while APIs are not? Do technologies have certain intrinsic qualities that determine the extent to which they are political?

Thomas Gieryn (1995) provides an explanation that moves away from such essentialist explanations: the demarcation between the technical and the political is the result of boundary-work. Boundary-work is the act of distancing the scientific or technical from the social. Gieryn describes how successful boundary-work results in the prevention of the control of certain technoscientific activities by outside powers. As political pressure on Apple and Google was mounting to cooperate in the development of contact tracing apps, it was not unthinkable that they would be forced by nation-states to adapt their operating systems to accommodate these apps. Whether this would have been attempted by court order remains unknown, but the reputational risk of being seen or characterized as the impediment to public healthcare in a global pandemic was all too real. An attempt at such a characterization happened only later, on the 5th of May, when France’s minister for digital technology, Cedric O made some hefty accusations against Apple (Kar-Gupta & Rose, 2020):

Apple could have helped us make the application work even better on the iPhone. They have not wished to do so. I regret this, given that we are in a period where everyone is mobilised to fight against the epidemic, and given that a large company that is doing so well economically is not helping out a government in this crisis. We will remember that when time comes.

But already earlier it became crystal clear that states around the world were longing for contact tracing apps with reports about their development from Germany (Busvine, 2020a), France (Rose & Pineau, 2020), Israel (Cohen, 2020), Singapore (Ungku, 2020), South Africa (Dludla, 2020) and even a European effort (Busvine, 2020b). Meanwhile, Apple was all too aware of its privacy feature of limiting apps’ access to Bluetooth while not being opened and in the foreground. At least some form of action was crucial. In providing this API, Apple and Google have “kept politics near, but out” (Gieryn, 1995, p. 434). They have protected their autonomous control over their operating systems by providing political forces with just enough to prevent more threatening consequences. They engage with politics just enough to be able to contribute to societal problems and demonstrate their usefulness. However, they refrain from becoming entirely entrenched in the heated debate about contact tracing by not providing the apps themselves, therefore leaving the final implementation of the solutions to the public health authorities. This would allow Apple and Google to avoid risk of loss of prestige or credibility in the case of further controversies surrounding the contact tracing solutions. Developing the API, but not the app, is a clever maneuver which shows the skillful demarcation between the technical and the political. Not only are they walking the tightrope between these two territories — they have put it up themselves by constructing the boundary in a way that maximizes perceived beneficence and minimizes the risk of reputational loss, all the while maintaining full autonomy over their infrastructure.

Contested sovereignty and protocol politics

Even though Apple and Google are not directly engaged in developing the app, that does not hold them back from having a say in how the apps should behave. From their initial announcement of the new standard it was clear that they favored a decentralized approach: this is a central feature of the design of the APIs. Accessing the Bluetooth sensor’s data through the new API and storing it on a centralized server is not allowed. Apps that would do this would simply not be given access to the new API. A second limitation took longer to emerge. For weeks, the Silicon Valley companies remained unsure of whether they would allow contact tracing apps to combine the Bluetooth data with GPS data (Nellis & Dave, 2020a). It was only on the 4th of May that they finally announced that location data could not be used by apps that access their contact tracing API (Nellis & Dave, 2020b). This is in stark defiance of the explicit request of US states North and South Dakota and Utah to access location data. Simultaneously, a third limitation was introduced: only one app per country or region would be allowed. What exactly defines a region was not specified.

Theoretically, public health authorities could still decide to go without the new API and thus circumventing the newly imposed limitations on their apps. However, the importance of this API is rendered visible by examining Germany’s and France’s continued attempts at developing an app that does not rely on the newly proposed protocol (Rosemain & Busvine, 2020). They long desired a centralized approach which would give the respective governments far greater control over and insight into the collected data. Finally, Germany gave in to the desire for a decentralized approach and flipped (Busvine & Rinke, 2020). Colombia made a serious attempt to deliver contact tracing without Apple’s and Google’s API, but failed and dropped the contact tracing feature from their “CoronApp” after a month, planning to resume their program when the new API is ready (Dave & Nellis, 2020).

Evaluating infrastructures of healthcare: beyond privacy

Much public scrutiny appears to focus on the privacy implications of corona apps (Verhagen & van Gestel, 2020; Verhagen & Brouwers, 2020; De Wit, 2020). Function creep is one of the dominant aspects of these implications: while initially their only intended use would be to conduct contact tracing in order to contain the spread of the virus, governments and corporations could soon find other uses for the gathered data. The data in this case is highly sensitive and useful, a social graph of which people interact with each other. Replacing the word “infection” with “crime” directs our gaze at other potential use cases of this data (Parthasarathy, Stilgoe & Waisanen, 2020). If you have recently interacted with a criminal, there is a certain probability that you are also involved in criminal activity. Some may be satisfied by the guarantees that all data will be anonymized and only stored in decentralized ways. However, the potential applications of this data still remain: if a person can be identified as having been in contact with an infected person, she can also be identified as having been in contact with a criminal. Apple and Google have promised us that apps can only use their exposure notification API for contact tracing during the pandemic (Exposure Notification Frequently Asked Questions, 2020). However, the next time that governments will require this technology it will again be requested on the grounds of combating a crisis. And with crucial elements of the sociotechnical infrastructure already in place, the barrier to the adoption of this technology has been lowered significantly.

While such privacy concerns are not to be minimized and deserve careful consideration, we also cannot ignore the implications of building crucial elements of our public healthcare on top of an infrastructure that is under the tight control of Silicon Valley tech giants. By developing the API, but not the app, their political influence is disguised as the pure technological enablement of public health authorities to perform contact tracing in ways that seem appropriate to their locality. On closer inspection, however, we can observe that Apple and Google are still exerting significant power as system builders by controlling access to the infrastructure. And infrastructures last: their endurance is one of their fundamental qualities as they can last far beyond political trends and temporary crises (Edwards, 2010). Ever more elements will use the infrastructure as their foundation, strengthening the network as they are added. Eventually, the infrastructure’s endurance itself will function as its legitimization in a self-perpetuating cycle. The influence of Apple and Google on how public healthcare is conducted within the territories of nation-states might prove difficult to be rolled back once the pandemic is over, as Tamara Sharon (2020) has noted. She argues that our increased dependency on these tech companies for providing what used to be public services will ultimately lead in the reshaping of these services to more closely align with the values and interests of Silicon Valley. These may of course be at odds with those of European citizens.

In a crisis it is tempting to reach for technological fixes that promise to address our immediate concerns. However, we must not forget that these promises are based on technoscientific imaginations and not on empirical evidence. Coronavirus apps are strongly dependent on Bluetooth sensors, which are already known to be inaccurate and unreliable in measuring the proximity between devices. Furthermore, these apps are not created in a vacuum and they come embedded in a sociotechnical infrastructure. They can have long-lasting effects on the balance of power between tech giants and nation-states and have the potential to reconfigure the stage of geopolitics. It remains to be seen how these nation-states’ sovereignty will be affected when they hand over responsibilities to international corporations and increasingly come to depend on their computational infrastructures.

Thomas Kuipers is following the masters program of Science-Technology-Society and works as a software engineer on various projects, most notably in the cyber security space. He is particularly interested in how software is used as politics by other means.

References

Apple & Google. (2020). Exposure Notification Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved from https://covid19-static.cdn-apple.com/applications/covid19/current/static/contact-tracing/pdf/ExposureNotification-FAQv1.1.pdf

Bratton, B. H. (2015). Introduction. In The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (pp. 3-18). The MIT Press.

Busvine, D. (2020a). Germany aims to launch Singapore-style coronavirus app in weeks. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL4N2BN3MQ

Busvine, D. (2020b). Europe to launch coronavirus contact tracing app initiative. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL8N2BP1N0

Busvine, D. & Rinke, A. (2020). Germany flips to Apple-Google approach on smartphone contact tracing. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN22807J

Cohen, T. (2020). 1.5 million Israelis using voluntary coronavirus monitoring app. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN21J5L5

Dave, P & Nellis, S. (2020). Colombia’s coronavirus app troubles show rocky path without tech from Apple, Google. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN22J03W

de Wit, T. (2020). Corona-app is succes op Britse eiland Wight, weinig zorgen om privacy. Volkskrant. Retrieved from https://nos.nl/collectie/13841/artikel/2334651

Dludla, N. (2020). S.Africa launches mobile tracking of those with coronavirus. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL8N2BQ61L

Edwards, P. (2010). Thinking Globally. In A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data and the Politics of Global Warming (pp. 1-25). The MIT Press.

Gieryn, T. (1995). Boundaries of Science. In S. Jasanoff, G. Markle, J. Petersen, T. Pinch (Eds.), The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies (pp. 393-443). London: Sage.

Jasanoff, S. (2013). Epistemic Subsidiarity – Coexistence, Cosmopolitanism, Constitutionalism. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 4(2), 133–141.

Kar-Gupta, S. & Rose, M. (2020). France accuses Apple of refusing help with ‘StopCovid’ app. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN22H0LX

DeNardis, L. (2009). Scarcity and Internet Governance. In Protocol Politics (pp. 1-24). The MIT Press.

Nellis, S. & Dave, P (2020a). Showdown looms between Silicon Valley, U.S. states over contact tracing apps. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN22702F

Nellis, S. & Dave, P (2020b). Apple, Google ban use of location tracking in contact tracing apps. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN22G28W

Parthasarathy, S., Stilgoe, J. & Waisanen, E. (2020). Episode 6: COVID Knowledge, Technology, and Politics: Dispatches from Around the World. The Received Wisdom Podcast. Retrieved from http://shobitap.org/the-received-wisdom/2020/4/19/episode-6-covid-knowledge-technology-and-politics-dispatches-from-around-the-world

Renew Europe (2020). RENEW EUROPE Webinar on COVID-19 contact tracing applications. [Online webinar]. Retrieved from https://re.livecasts.eu/webinar-on-contact-tracing-applications/program

Rosemain, M. & Busvine, D. (2020). France, Germany in standoff with Silicon Valley on contact tracing. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN2262LM

Rose, M & Pineau, E (2020). France working on ‘StopCovid’ contact-tracing app, ministers say. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN21Q1D3

Sharon, T. (2020). When Google and Apple get privacy right, is there still something wrong? Retrieved from https://medium.com/@TamarSharon/when-google-and-apple-get-privacy-right-is-there-still-something-wrong-a7be4166c295

Stilgoe, J. (2015). Balloon Debate & Making Models. In Experiment Earth: Responsible Innovation in Geoengineering (pp. 1-20, 159-174). Earthscan from Routledge.

Ungku, F. (2020). Singapore launches contact tracing mobile app to track coronavirus infections. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN2171ZQ

Verhagen, L. & Brouwers, A. (2020). Nederlandse app-makers klaar voor corona-app. Volkskrant. Retrieved from https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/~bb2019b4/

Verhagen, L. & van Gestel, M. (2020. Apps kunnen helpen de coronacrisis te bezweren, helpt dit de privacy om zeep? Volkskrant. Retrieved from https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/~b9bac9d0/