So, we made a zine. We – that is Ariadne, Bao-Chau, Esther, Sarah, Fredy, Andrea, Kathleen, and Constantin – are all working at the University of Vienna’s Department of Science and Technology Studies (STS). But what is a zine? Why did we make one? And what does this have to do with Science and Technology Studies (STS)?

Zines – a kind of booklet – are crafted pieces of work composed of text and different visuals. The text can be produced in various ways, e.g., through writing by hand or by using digital tools. The visuals can consist of a wide range of forms, again, from drawings by hand to photographs or digital images. In contrast to clear-cut formats like journal articles or other more established forms of publications, these textual and visual elements are often arranged in overlapping and interlocking (one might even say messy) ways. Once produced, zines are circulated among a rather small group interested in the same issue (Kempson, 2015).

In our case, the starting point for producing a zine was a call for contributions to the ‘DIY Methods 2022’ conference, a mostly screen-free, zine-full and remote-participation conference on experimental methods for research and research exchange organized by the ‘Low-Carbon Research Methods Group’[1]. On their website, the group describes itself as a “loosely-affiliated network of scholars interested in examining how climate change not only stands to alter what we study, but how we do so”. While a variety of academic disciplines and approaches is present in the group, Anne Pasek, the director, also draws on feminist STS to discuss regimes of fossil fuels and aviation in contemporary academia and points to some pathways for change (Pasek, 2020).

One way of thinking about carbon in academia is by critically engaging with the research methods that are applied to study it. This not only refers to the natural sciences but also our own, social science methods. This gave us the idea of using the call to reflect on an ongoing, collective, and collaborative autoethnography about mundane academic practice in pandemic times. If you want to get another perspective on this process, check out an earlier post on this blog by Esther Dessewffy and Bao-Chau Pham where they explore how this endeavor shapes care practices and researchers’ identities. By crafting a zine, we now aimed to express our experiences, emotions, and thoughts about our daily lives in academia in a, for us, very different format than we usually work with and in an attempt to share our research methods in a low-carbon way.

In this blog post, we want to share some reflections on the process of making our zine and participating in the conference. In doing so, we want to draw your attention to three moments of reflection: first, zines act as collaborative tool as well as a way of doing and sharing research. Second, making zines emphasizes the processual and everything-else-than-linear character of doing research, exemplified by a series of visuals from our own process. And third, we give insights into the advantages, limitations, and complexities of contributing to a conference that is not held in-person or digitally but taking place through the distribution of the zines via post and through discussions on social media.

Zines as tools in research

While there were and are many ways to do social science research, and many ways to share it, STS scholar Sergio Sismondo (2016) has pointed to the rise of “new venues in STS” by exploring different emerging publication formats which complement traditional publishing in journals and books. Zines can be understood as one such venue. While some researchers describe zines as “queering the form” and point to their methodological and material aspects (Damon et al., 2022), others frame them as a situated and context-specific form of Do-it-Yourself (DIY) feminism (Kempson, 2015).

For our zine, we also drew on the notion of the pinboard and logics of juxtaposition (Law, 2007) to emphasize the non-linearity of crafting arguments in academic research – for a more elaborated discussion of this see a visual essay here. Crafting a zine is not only about sharing and publishing research results or knowledge, but is itself a process of thinking, improvising, and learning.

The process – pinboards in the making

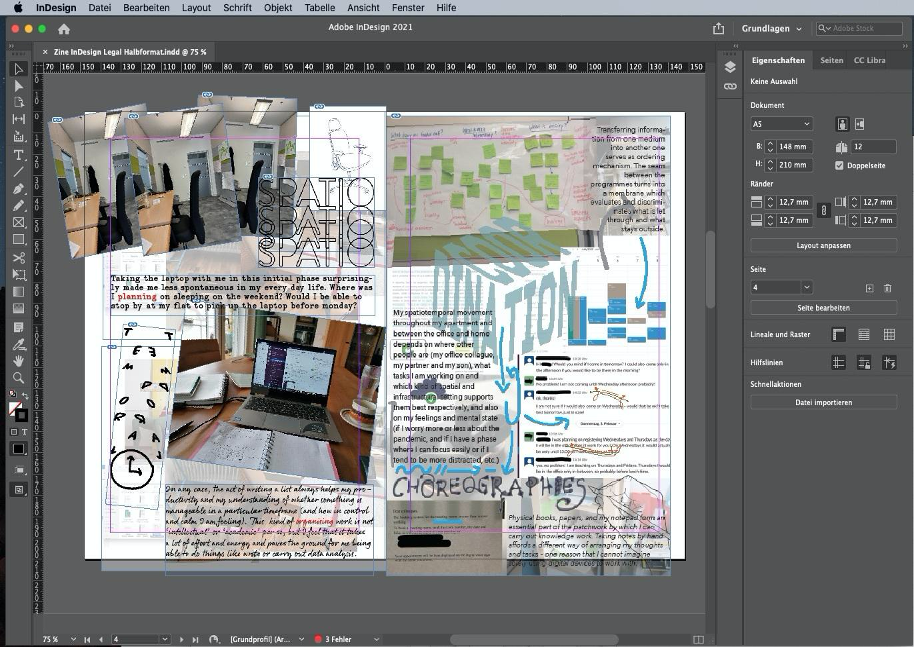

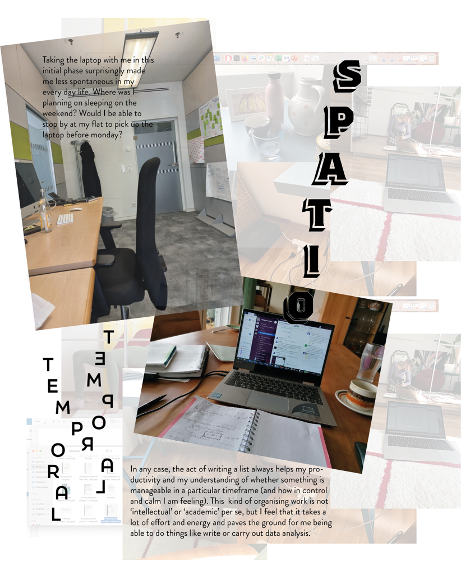

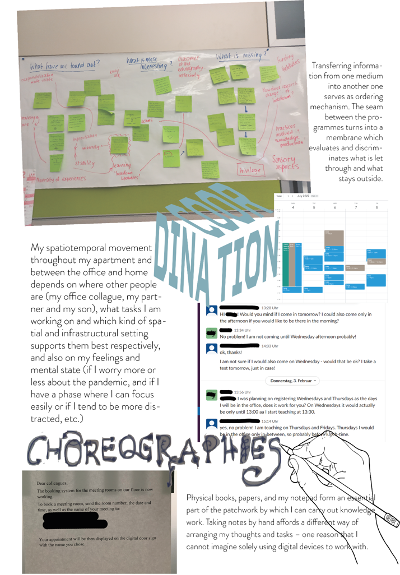

The attempt to craft a zine consisted of individual and collective efforts, and made use of a variety of materialities, digital tools, and, more generally, a constant re-thinking, re-ordering, and re-positioning. This not only applied to text and visuals, but also to ourselves, our ideas, and our own situatedness (Haraway, 1988).

The following series of pictures tries to show how different forms of writing and visualizing are interwoven in the process of making our zine. Below, you can see snapshots from the making of one of the pinboards. Other pinboards in our zine are completely different – not only in terms of outcome but also in the process. This is due to the decision we made that individuals should take the lead on the different pinboards but, at the same time, we acknowledge that we build on and engage with the experiences, knowledge, and work of everybody in the group. This approach should, on the one hand, deliberately allow for non-linearity, non-consistency, and non-coherence to evolve and, on the other hand, emphasize that knowledge-production is never solely individual but always a social process, especially in such a collaborative project.

The chosen pictures can be seen as an imperfect attempt to make some of our processes visible and understandable, although many facets are left out here.

Participating in a different conference

By contributing our zine to the DIY methods conference, we were also invited to participate in a series of events over the summer.

First, the Low-Carbon Research Methods Summer Institute organized by Alexandra Lakind & Kate Elliott, seasonal scholars of the group, offered an office hour to provide a space for reflecting on carbon-intensive practices in research. The aim was to discuss predominant norms and expectations in academia but also to think about alternatives. My colleague Ariadne Avk?ran and I together decided to register for such an office hour and were eager to learn more about the role of carbon emissions in research. In the meeting then, we were surprised to be asked a set of questions about our own research and daily lives, especially considering carbon practices. We did not really expect this, but it led to a reflection not only about our individual practices but also regarding institutional settings, disciplinary norms, societal contexts, and political opportunities for change.

Interested in engaging with these issues further, I participated in a subsequent online workshop with the aim to explore low-carbon tools and techniques. Now, finally, I would get the answer on how to be low-carbon in my research practices, right? At least that is what I thought.

But, again, it turned out differently. One first surprise, for me, was that in this virtual space roughly half of the workshop was devoted to getting to know each other in small breakout rooms. It was nice and interesting to chat with people from different geographical, disciplinary, and institutional backgrounds, but I was starting to wonder if I would get the answers and solutions I was hoping for. During the second part of the workshop, though, the variety of perspectives I encountered in these conversations helped me to realize that there are many (more) realities and ideas of both problems and solutions for doing research in low-carbon ways. To know a bit about other participants’ situatedness not only made me aware of new aspects, but also contextualized the issues that were raised in the plenary and achieved more understanding amongst participants. Topics and issues that emerged – and these are by far not all – ranged from energy infrastructures to different ways of traveling, from institutional contexts to disciplinary norms, from global issues to local ones, and from digital aspects to embodied experiences.

For me, this workshop opened up more questions rather than offering answers. I had hoped for some tools and approaches I could use in my own research practices, but the conversations took a more theoretical turn. However, this also made me aware of the difficulty to provide ready-made and easy solutions for the complex and context-specific situations people are in when trying to research in low-carbon ways. One key learning for me – and this might be obvious, but I think it is still important – was that I cannot expect to just receive the perfect solutions for me from others, not on this day but most likely also not on any other day. Rather, this workshop led me to reflect on carbon in my own research practices more frequently and think of it as an ongoing process.

And then, finally, it was time for the DIY methods conference itself. All the digitally submitted zines were printed out by the organizers and sent to the participants across the world. So, there was not a physical gathering of people in one place but instead a physical gathering of peoples’ zines at different places. It was delightful to look at all the zines and be able to engage with other participants’ reflections and the ways they had been materialized. To further explore the methodological experiments the participants crafted through their zines, a virtual discussion took place on Twitter to avoid Zoom and issues with different time zones. After a couple of initial kick-off Tweets by the organizers of the conference, some threads unfolded and led to interesting conversations, for instance about how to carry out research in low-carbon ways despite established and institutionalized norms. However, I did not participate in the way I had hoped for because of my cautiousness and reluctance to engage on Twitter more actively and, in this case, the flexible and non-simultaneous manner of discussion was not a perfect fit for me.

Thinking about my own preferences and reflecting on other conferences I attended, I asked myself: What ways of doing conferences enable me to participate actively? Would I have been more active in a physical gathering? I am not sure and that comes with a lot of traveling, carbon emissions, money, and many other issues involved. Or would it have been any different on a different digital platform like Zoom? Again, I am not sure as such platforms also come with time zone differences, affordances of digital infrastructures, fatigue, and other issues.

I was puzzled. I realized that my previous assumptions about different types of conferences were much more complex than I thought. Personal, environmental, financial, institutional, disciplinary, political, and other considerations all play a role in this.

In the end, nevertheless, I have to say that I learned a lot throughout this whole process: about zines, academia, conferences, carbon emissions, my own preferences and practices, and much more. Exploring the entanglements of bodily experiences, materialities, and the digital proved to be a pathway worthwhile pursuing both while making our zine and when participating in the conference. To me, it seems that zines – as one venue of and for STS – can be tools for thinking and crafting ideas in research, but they also offer moments of reflection and, thereby, point to different ways of doing and sharing research. Though, of course, they are not a perfect fit for everyone, and every piece of research!

If you want to take a look at the zines produced for the conference, you can find them here.

And in case you got interested in the work of the Low Carbon Research Methods group, Kate Elliott is taking the lead on the ‘Wayfinding for Restorative Methods’ initiative that emerged from the summer institute.

[1] The latter website is powered by a solar panel near Trent, Canada, based on the shared Solar Protocol.

References

Damon, L., Kiconco, G., Atukunda, C., & Pahl, K. (2022). Queering the Form: Zine-Making as Disruptive Practice. Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies, 22(4), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/15327086221087652

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Kempson, M. (2015). ‘My Version of Feminism’: Subjectivity, DIY and the Feminist Zine. Social Movement Studies, 14(4), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2014.945157

Law, J. (2007). Pinboards and Books: Juxtaposing, Learning and Materiality. In D. W. Kritt and L. T. Winegar (Eds.). Education and Technology: Critical Perspectives, Possible Futures (pp. 125–150). Lanham: Lexington Books.

Pasek. (2020). Low-Carbon Research: Building a Greener and More Inclusive Academy. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, 6, 34–38. https://doi.org/10.17351/ests2020.363

Sismondo, S. (2016). New venues in STS. Social Studies of Science, 46(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312715625854

Constantin Holmer is a master student in the STS program at the University of Vienna and a student assistant working with Prof. Sarah Davies. He is interested in (digital) academic practices and environmental issues.