by Lisa Lehner

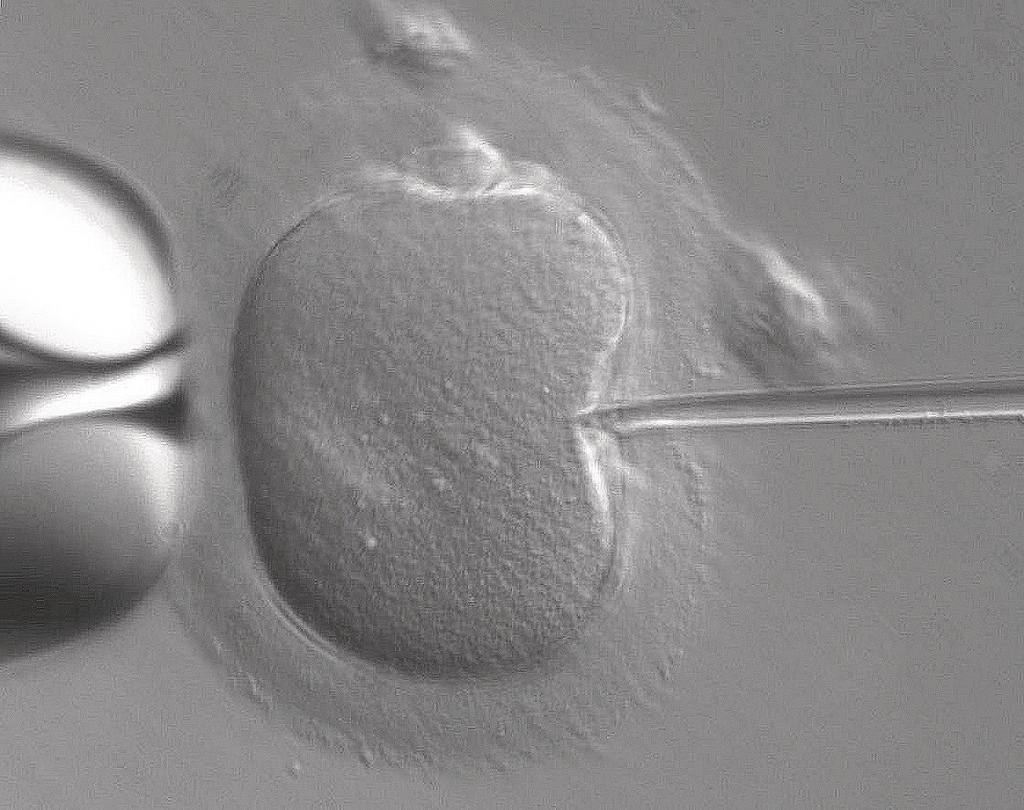

Austria just changed its cornerstone law on assisted reproduction and it’s a big deal. The “Fortpflanzungsmedizingesetz (FMedG)” [1], virtually unchanged since 1992, will now give women in same-sex partnerships access to assisted reproductive treatment, extend the use of third-party gamete donations and allow pre-implantation diagnostics.

That’s the stuff of big debates, one would think. In retrospect, however, not much talking happened at all. After a Constitutional Court decision it took the government about a year to react. Running on a deadline, then, the revision felt rushed and was capped off with a severely shortened review phase before the new law entered parliament last December. It has become somewhat of a pattern in matters of assisted reproduction that broader socio-political debates in Austria are, at best, rather subdued.

This is problematic at least for two related reasons: For one, this approach fails to appreciate as voices worthy of being heard the lived realities of people who have undergone, are undergoing or are unable to undergo assisted reproductive treatment. Secondly, excluding these voices also fails to recognize a variety of issues as meriting consideration.

Meanings of access. Without question, many people are still denied access to assisted reproductive treatment. While the law has opened reproductive leeway for women in same-sex partnerships, the same cannot be said for men in similar circumstances. This moves the logics of exclusion beyond the argument of homosexual vs. heterosexual reproduction. The question of equal rights for male same-sex couples is being displaced, preempted by a seemingly untouchable ban on surrogate motherhood. On the other end, not extending access rights to single men and women explicitly discounts a common familial reality in contemporary Austrian society. Many commentaries have raised red flags on these issues, and for good reason.

There is more to assisted reproduction than access rights, though. Overall, assisted reproduction in Austria is perceived as ultima ratio – only in case ‘natural’ reproduction fails. Assisted reproduction is seen as reproductive necessity, not choice. Its current legal, institutional and procedural organization demands that, for the most part, couples wishing to undergo treatment have ‘something wrong’ with one or both of them in strictly medical terms.

These powerful notions of ‘naturalness’ severely clash with decades of feminist critique against them. Yet, neither can the very real consequences be brushed aside that arise for people, for their self-perception and lives, when faced with legally and institutionally enforced diagnoses of reproductive failure. The FMedG-changes don’t interfere at all with this underlying tenor of ‘deviance’ and ‘artificiality’ opposing ‘nature’, nor with actively creating stories of bodily ‘faultiness’. Access rights alone cannot change this, for they cannot change these broader social connotations faced by those already in possession of these rights.

Biological clocks? Another topic frequently disregarded are imaginations of female biology. The ‘biological clock’ has proven to be particularly powerful in this respect. The schematic at play here, especially in assisted reproduction, is one of deterioration: Women only get so many eggs from the start, an ‘egg reserve’ decreasing over time. At some point (at around 40 years, it is said) women don’t have enough eggs left that would promise high reproductive success. The biological clock is a countdown, a deadline for one’s eggs: an egg timer, really.

This egg timer tasks women with managing their lives accordingly. Thus far, this task has been an all-or-nothing matter, for any ‘fault’ with women’s eggs, or any related issue warranting egg donations or a surrogate, ended at Austria’s ban on oocyte donations and surrogacy. What is more, this egg timer fosters economic disadvantages insofar as public finance limits its support for in-vitro-fertilizations [2] to men under 50 and women under 40. Because assisted reproductive treatments are costly, and IVF even more so, this legal reality vehemently terminates reproductive endeavors when women hit 40 – that is, only if one lacks the personal funds to continue indefinitely. Now, while the FMedG-changes bring the possibility of oocyte donations, they do so not without introducing their own age-limits for donors (30) and for receiving donations (45). And surrogacy, as it is, continues to be the matter non-grata.

Concisely argued reasons exist for all of these limits. These reasons are voiced by the Bioethical Review Committee, by medical professionals or by lawmakers and they are closely entwined with success rates and risk talk of a certain kind. Too often, however, they drown out the voices of those who have to live according to pressures posed by egg timers built into their gendered biology and drowned out is what this means for them.

The manner in which assisted reproduction is being talked about comes with its own reality of naturalness vs. artificiality, entails highly consequential diagnoses for people undergoing treatment and awards primacy to certain reasons why children can(not) be while obscuring others. Still, continuing not to talk at all is muting a variety of issues in favor of quietly accepting and reproducing patterns that should be more inclusively problematized.

For what it’s worth, my comments certainly leave much room for debate – and what a welcome change that would be.

References

[1] Federal Law on Reproductive Medicine, see Legal Information System of the Austrian Federal Chancellery; for details on the amendments see also the Federal Law Gazette (Bundesgesetzblatt) published on February 23rd, 2015 (German only)

[2] Assisted reproductive treatments generally do not garner public financial support. Yet, the IVF-Fund-Act provides means to alleviate the financial burden of in-vitro-fertilizations, see Legal Information System of the Austrian Federal Chancellery (German only)

Lisa Lehner received her Master’s degree at the Department of Science and Technology Studies in Vienna. Currently a graduate student at Cornell University, she continues to think about research ethics, temporalities, biomedical issues more generally and particularly about the bodies that matter in them – and about those that don’t.